CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT

INTRODUCTION Concept development is an important step in the overall design process. An exploration of ideas generated by the literature and case reviews, it is an opportunity to put pen to paper and see how different ideas and design approaches can be applied to the site in question. The process is intended to consider existing site conditions, programmatic requirements, and other factors into an organized, exploratory look into design possibilities for the site solution. Especially within the confines of an existing site and layout, it is important to look beyond what currently exists, and try to meet current and anticipated programmatic needs.

Concept development combines aspects of the literature review, case studies, and site analysis to create a cohesive whole that attempts to address different opportunities and challenges across the site. Each concept can specific conditions, but may incorporate all program elements and site conditions. A final concept will incorporate strengths and weaknesses from the individual concepts to address the most pressing needs and concerns about the site, while providing a framework for the site design to come. This process is iterative and an exploration of spatial ideas, all of which may or may not be incorporated into the final concept but can be evaluated on an individual basis to determine whether or not it is the preferred design solution. From a final concept, a site design can be undertaken in greater detail and focus. |

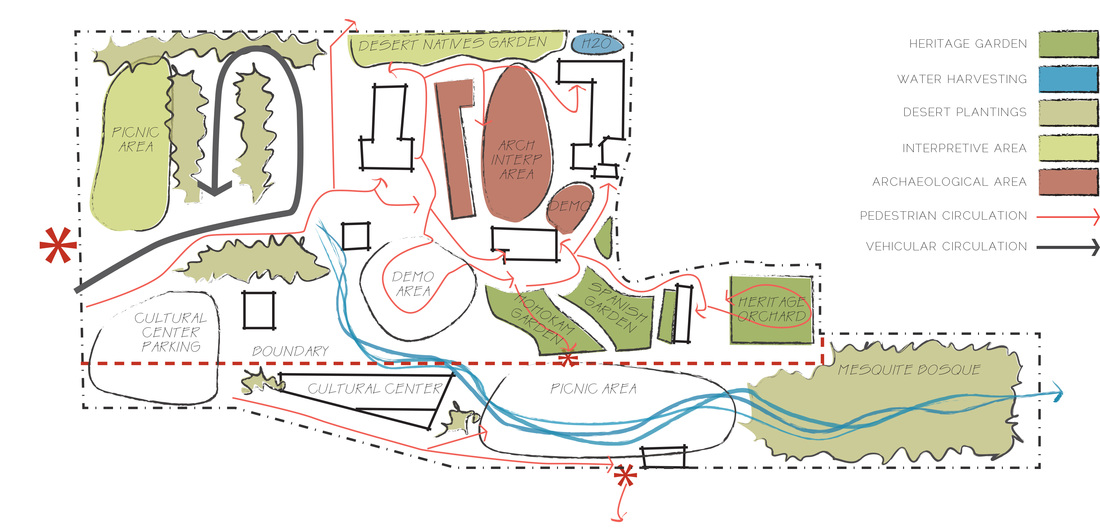

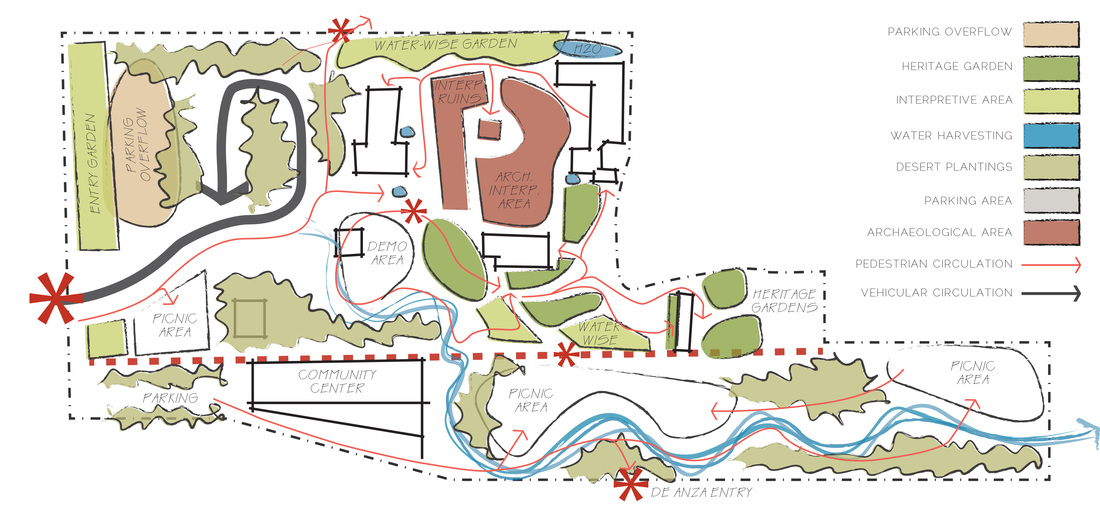

CONCEPT ONE | OF TWO MINDS

The first concept, ‘Of Two Minds’, conceives of the park in two parts; one, an enclosed, pay-for-entry historic park showcasing archaeological remains, the museum, and other preserved buildings and interpretive areas, and the second, a publicly accessible area, including parking, picnic areas, interpretive trails, and a community center. The historic portion of the site incorporates more planted areas, including ethnobotanic and heritage gardens, especially highlighting the cultural remains of the prehistoric occupants of the area. The pathways and gardens also seek to create connections between the buildings, not just pathways from one to the other. Enhanced interpretive areas and demonstration areas can be used for living history recreations and other events. A water harvesting area runs through both section of park, gathering stormwater from parking lot runoff to create a riparian interpretive area that visually and metaphorically connects the park to the Santa Cruz River, and can serve to interpret the river within the boundaries of the park. The more public side of the park will create public areas that are accessible and can connect the park to the community, as well as providing space for events and other rentals. The community center will serve as that indoor rental space, and families can use the picnic areas on the weekends. An interpretive pavilion is proposed for the intersection of the site and the De Anza Historic Trail, establishing the park as an important trailhead for this recreational area.

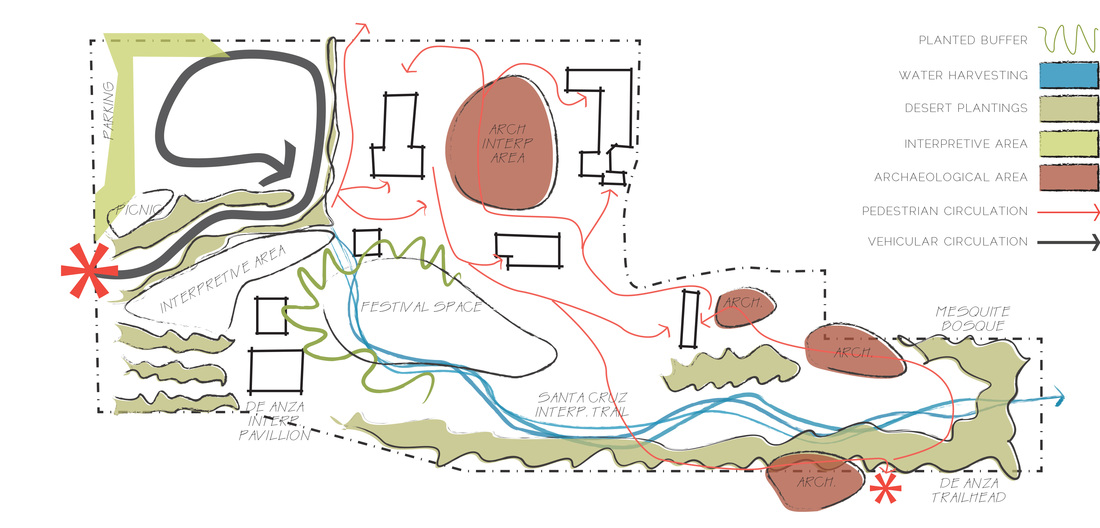

CONCEPT TWO | HISTORY FIRST

The second concept, ‘History First’, focuses mainly on the historic interpretation and built and archaeological remains of the site. Trails are directed throughout the site based on the location of archaeological remains, which would be rehabilitated and interpreted (currently the access is blocked and there is no interpretation for minor archaeological sites). A variety of trails are provided, including those that travel through the more established areas of the park visiting the buildings placed on the National Register, whereas more interpretive trails travel through the lower parts of the site, visiting different archaeological remains and passing along the De Anza trailhead. Another interpretive trail addresses the role of the Santa Cruz River in the history of the site along the stormwater runoff that is gathered from the parking lot. This riparian zone will terminate in a large, existing mesquite bosque, which reflects the earlier natural environment of this area. Large areas are provided for interactive interpretive efforts; living history demonstrations, festivals, and adobe demonstration areas can all serve a variety of users in the different spaces, providing space and flexibility for programming opportunities. The parking lot is also somewhat reconfigured, providing less opportunity for vehicular and pedestrian conflict, while creating more vegetative buffer between the parking lot and the surrounding historic site.

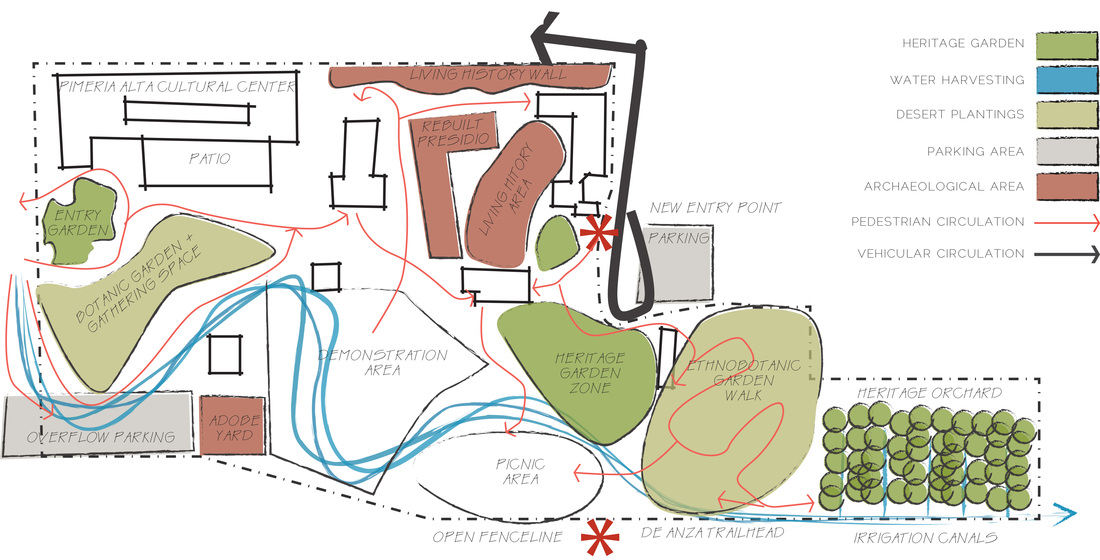

CONCEPT THREE | LIFE ZONES

The third concept, “Life Zones”, focuses more on the natural and environmental history of the site and proposes to interpret those areas for visitors. It also focuses on interpreting the built history of the site as well, emphasizing the connection between the cultural and the natural world. One main change in this concept is the relocation of the entry plaza, towards the east end of the site, near the now-unused turnaround. This would give visitors the opportunity to first visit the museum and get a better understanding of the site, before proceeding to the physical remains. This concept also proposes a large cultural center on the site of the former parking lot, turning asphalt paving into a botanic garden and gathering space for events and other uses. This redirected space also creates an opportunity for more interpretive efforts; an adobe yard to provide hands-on experiential learning serves the dual purpose of creating adobe bricks for the rebuilt presidio walls. The former archaeological area is turned into a living history demonstration area. Also incorporated are a series of interpretive gardens, focusing on ethnobotany, heritage gardens, and a heritage orchard that demonstrates early irrigation techniques as well as giving visitors an opportunity to taste history. These heritage gardens have circulation paths between and throughout them, providing visitors with an ever-changing experience that highlights all of the senses while interpreting the less-visible story of early agriculture in the Santa Cruz River Valley region.

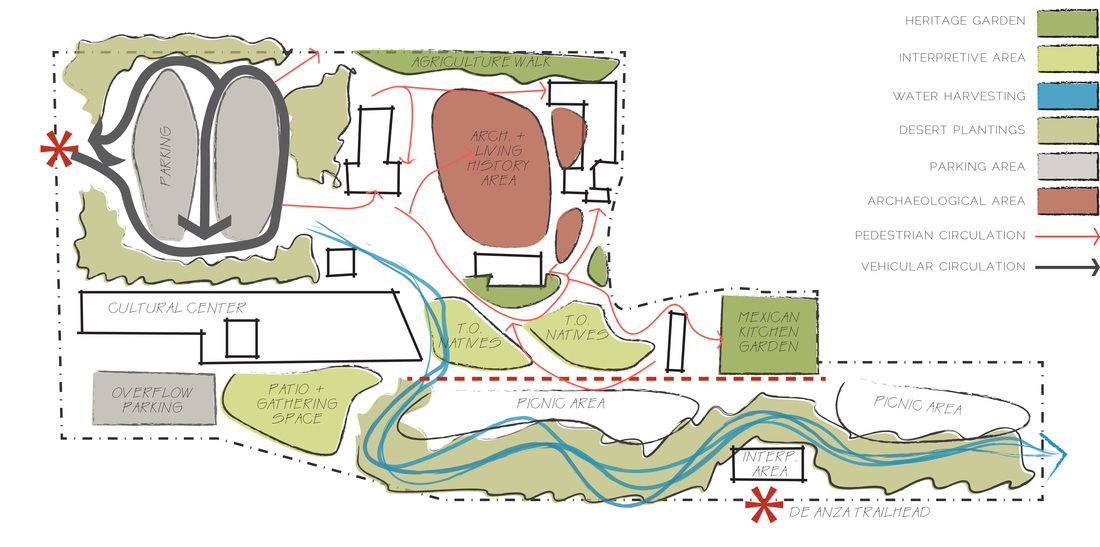

CONCEPT FOUR | CULTURAL CENTER

The fourth concept, ‘Cultural Center’, proposes a significant built addition to the park grounds, a cultural center, which can provide formal event space on the grounds of the park to address the needs of the park as an event and cultural gathering space. This concept also proposes a division of the park into public and private areas; one for the historic and cultural interpretation of the site, and the other to provide a gathering space and recreational facility for locals and other visitors. The cultural center will create an additional income generating opportunity for the park, to be leased out for events, but also to serve as a headquarters for trips and other cultural events planned by the park. The picnic areas will be publicly accessible and have their own dedicated parking lot. An interpretive pavilion at the trailhead of the De Anza trail will cement the role of De Anza in the development of the Tubac Presidio and provide additional recreational facilities at the park.

The entry sequence of the park from the surrounding village of Tubac will be reconfigured; now, visitors will see an inviting cultural center building and gardens instead of the entrance to a parking lot. Reconfiguring the parking lot will reduce the amount of impermeable paving whiles still providing plenty of parking for park visitors. Once inside the park, visitors will experience a number of different interpretive areas, ranging from the archaeological to the ethnobotanical. A variety of created garden spaces will showcase the variety of people who have called this site home; the floodzone agricultural areas of the Hohokam and their Tohono O’odham descendants; the kitchen gardens of the Mexican cattle pioneers, and the heritage gardens of the later European settlers.

The entry sequence of the park from the surrounding village of Tubac will be reconfigured; now, visitors will see an inviting cultural center building and gardens instead of the entrance to a parking lot. Reconfiguring the parking lot will reduce the amount of impermeable paving whiles still providing plenty of parking for park visitors. Once inside the park, visitors will experience a number of different interpretive areas, ranging from the archaeological to the ethnobotanical. A variety of created garden spaces will showcase the variety of people who have called this site home; the floodzone agricultural areas of the Hohokam and their Tohono O’odham descendants; the kitchen gardens of the Mexican cattle pioneers, and the heritage gardens of the later European settlers.

FINAL CONCEPT | HISTORY MADE MODERN

|

The final concept, ‘History Made Modern’, compiles the most successful elements of previous concepts, while attempting to eliminate problems and causes of conflict present in other concepts. Though many different ideas have been explored in previous concepts, some elements were present throughout the conceptual design, and these reoccurrences are significant, as they represent what ideas are the strongest.

In consideration of the park’s need for different areas of development for increased economic benefit, the site has been divided into two parts to allow for outside sources of revenue generation. The historic buildings, archaeological sites, and the museum all remain on the historic site of the state park, where a paid entry fee allows visitors to access the historic sites and the museum. This represents little change in the park’s current mission, and will not exclude anything from the park that was not present before. It also guarantees a day-to-day source of income that can be applied towards the growth and maintenance of the historic assets within the state historic park. Reconstruction has been rejected as a possibility for this site, as there is not enough historic evidence to justify a reconstruction of the presidio walls. Instead, adobe building and interpretive areas have been moved to other areas of the park, where they can still be accessed for interpretation and maintenance purposes, but do not create the issues with authenticity that a reconstruction of the Presidio walls would surely invite. A different sort of interpretation and visualization will be proposed for the archaeological sites. The second, southern section of the park creates a piece of the park more focused on recreation and providing physical amenities. A dedicated community center is the center of these public amenities, allowing for programming options from the park, but also providing opportunities for community groups, private event rentals, and other public uses. This community center could also host year-round amenities, like a small café, or bicycle rentals for the nearby De Azna trail system, making it a destination for a wide variety of activities. A dedicated parking lot for the community center also feeds into a trailhead and interpretive pavilion for the De Anza trail, orienting visitors to this multi-state historic route and providing opportunities for walking, biking, and other recreational uses. A picnic area allows for public use by visitors and community members, but also can be accessed by groups from within the historic side of the park, a perfect amenity for visiting school groups. The picnic areas have been broken up into several areas of different sizes to accommodate multiple groups. The public accessibility and picnic areas reach back to when the state park was publicly accessible, and did not have to rely on visitor entry fees for revenue, allowing nearby residents to once again consider the state park an integral part of their community. |

The Santa Cruz interpretive trail is the major element that connects all of the pieces. Primarily a conduit for managing stormwater runoff, this series of microbasins creates an area for interpretation of the desert ecosystem, and provides a direct link to the Santa Cruz River, out of site but an integral part of the history of the Presidio. Though it is not a recreation of the river itself, it can serve to illustrate the importance of the river in the prehistoric occupation of the site all the way to its present-day incarnation. It can also illustrate stormwater management principles to students, residents and visitors from out of town who are not familiar with the fleeting ephemerality of water in the desert, and how the desert dwellers have adapted their practices to take advantage of a scarce resource.

The parking lot is reduced in size of asphalt paving, reducing the heat island effect and improving water runoff quality. Though two rows of parking stalls remain, the third row of parking stalls is transformed into a multiuse area, and can function as overflow parking when needed but also for famer’s market stalls or other interpretive events. Paved in decomposed granite, it can also serve an educational importance about the effect of impermeable surfaces in the urban heat island affect. As this parking is rarely used at its full capacity, this opens a large, flat and accessible area to other programming purposes. Adaptation of the current parking lot arrangement can create more suitable habitat for native species in planting basins, fed by stormwater captured from curb cuts and other water harvesting techniques. This will also help to create shade for the parking lot, beneficial to both cars parked in the lot and their human occupants. This concept seeks to unite historic destinations, creating an interpretive whole, instead of just chapters of a story. Heritage, water-wise and ethnobotanic gardens showcase the story not seen in the historic buildings and archaeological remains, and provide interest for visitors throughout their journey through the historic park. Educational opportunities are expanded for visiting groups, and seasonal change gives them a reason to return. This concept seeks to unite journeys between interpretive destinations, providing an opportunity for education, inspiration, and wonder, every step of the way. |