CASE REVIEWS

INTRODUCTION Case reviews present an opportunity to apply lessons and guidelines from the literature review to real-world cases, where these guidelines and attributes can be evaluated for their successes and failures. These case studies are not specific to one area of investigation in the literature review; many of these sites combine elements of interpretive design, small park design, cultural and historic park design, and heritage gardens, as well as archaeological remains and reconstructions. Some case reviews have just one or two of these elements, and some have all of the above. This is because none of these elements exists in a vacuum, and successful parks combine all of these elements into a greater whole. They also serve a function in that a project cannot be evaluated before it is built, and case studies can function as a stand-in for an in-depth project review after the fact.

The importance of conducting case reviews in the overall conceptualization and design of a site plan is to apply the lessons from the literature review, through the case reviews, onto the eventual site design. This research is indented to function as a sort of proof-of-concept for any design decisions made for the final design. |

FORT LOUDON STATE HISTORIC AREA

Fort Loudoun is a mid-18th century British fort in Tennessee that has since been designated as a State Historic Area. The fort was occupied originally between 1756 and 1760, and was eventually abandoned and overgrown, although it remained an important landmark locally. Archaeological excavations conducted under the auspices of the WPA found some historic remains. Interpretation efforts at that point included an artifact display, a brochure, and a self-guided walking tour. When the Tennessee Valley Authority threated to flood the site, extensive research was undertaken, both archaeological and historic, and enough information was found to appropriately guide reconstruction efforts, which commenced in 1960. The area that now comprises Fort Loudoun State Historic Area was saved from the flooding, but the ensuing lake completely altered the surroundings of the site. As the site was largely reconstructed, and because of the lack of original historic material, there was no need to protect fragile archaeological remains. Themes of interpretation were selected for the site; these included the natural environment of the valley, the history and occupation of Fort Loudoun, and the archaeological remains, as well as the fort reconstruction itself. As the site is used mostly by tourists and school groups, the reconstruction of the site allows for easier interpretation of the site, a more complete educational resource for school demographics, and enhances awareness of the historic past. Living history weekends and events serve to reinforce the interpretive efforts for this demographic, among others. The site also attracts visitors for more than just history; people in search of fall colors or water-related recreation also visit the site (Distretti and Kuttfruff 2004).

Design Implications Reconstruction should only be undertaken in instances where the historic record is complete enough to allow reconstruction to proceed in an informed fashion. In this case, the research did allow for this method of interpretation, which is a benefit to a wide variety of visitors who may find the historic remains of the site easier to understand if they are made visible. Ease of interpretation encourages school groups and other educational users to visit the site. The site creates opportunities for recreation outside of historic site visitation. Reconstruction can take place at a site where there is no longer any visible evidence; recreating the evidence is enough to restore interest in the site. |

BENT'S OLD FORT

Bent’s Old Fort was a trading post built of adobe located on the mountain branch of the Santa Fe Trail that largely dealt in the fur trade. The reconstructed fort is located near modern-day La Junta, Colorado, is unique among many historic sites in that it is entirely constructed of adobe. The fort itself was abandoned and partially burned in 1849, rehabilitated in 1861 and turned into a stage station, and then left to melt in the elements again in 1881. What little remained of the adobe buildings was cleared off of the site in the 1921 Arkansas River Flood. The Daughters of the American Revolution purchased the site, and donated it to the Colorado Historic Society in 1954. When it came under the ownership of the historic society, the “site was excavated partially…to create an interpretive exhibit utilizing the exposed adobe foundations on stone footings” (Wheaton 2004:217). As the site was left to the elements, the adobe eventually eroded, leaving no material behind above grade. Reconstruction efforts were funded in 1973, and enough original material was uncovered through research efforts to allow the reconstruction of the site. As with many adobe projects in this era, the reconstruction team used cement to seal the adobe bricks, eventually leading to structural issues within the adobe walls. The Colorado Historic Society had initially intended to replace the plaster yearly, for demonstration and interpretation purposes, but yet again the weather intervened, and eroded the reconstructed building away. The National Park Service took over stewardship of the site in 1973 as it had become too much for the Colorado Historic Society to manage (Nps.gov). The constant reconstructions of the site created a problem with the perceived authenticity of the site, and became an ongoing maintenance problem. While the reconstruction efforts may have been flawed, in the end it was done in the interest of the public, as “no off-site reconstruction can convey the experience of walking on ‘hallowed’ ground” (Wheaton 2004:230).

Design Implications In reconstruction projects, especially those involving adobe construction or something that needs constant, permanent maintenance, it’s important to plan well in advance for those maintenance requirements, as well as for anticipated future use of the site. Reconstructions allow the public to more easily interpret the site, and to better understand its history. Adobe can present an issue, especially in areas with heavy rains or flooding potential. Reconstruction efforts that are only half-realized may muddy interpretation efforts, calling into question the authenticity of the site, as well as the reconstruction efforts themselves. |

RIO GRANDE BOTANIC GARDEN

The Heritage Farm at the Rio Grande Botanic Garden in Albuquerque, New Mexico, recreates a 1930’s era Albuquerque farmstead, with kitchen gardens, orchards, vineyards, as well as reconstructed farm buildings. This interpretive garden is part of a larger botanical garden whole, the mission of which is to educate and interpret the cultural and natural heritage of the area for its visitors. As part of the greater mission of the Rio Grande Botanic Garden, the Heritage Farm interprets a very specific period of time in this particular place, and interpretive programs take place at the farmhouse itself (cabq.gov). Among other heritage products, this farm grows mission figs, Sonoran pomegranates, Navajo-Churro sheep, and Spanish turkeys, as well as raising many varieties of heirloom vegetables: chapalote popcorn, amaranth, tepary beans, and acorn squash. These crops are grown on-site, and the reconstructed stables are home to a variety of livestock that live on site. These heritage varieties is that they are already adapted to the dry, desert environment and they continue to adapt to new desert conditions as they are continuously grown, which helps to preserve the overall genetic diversity of food crops, especially those that are adapted to climatic extremes. People are actively seeking out locally produced heritage products, which create demand for these goods, while supporting the farmer and practices and educating the public as to the importance of these heritage food products (Nabhan 2010).

Design Implications There is currently demand for locally-produced heritage products, and exhibits that showcase the relevance and history of those products serve to reinforce and grow the demand. Historic heritage gardens are important in preserving the genetic diversity and evolutionary advantages of desert plants, and they can create an opportunity for education of visitors and the public. Heritage gardens can give visitors the opportunity to interact with, hear, and taste history in heritage gardens. |

HISTORIC TUMACACORI ORCHARD

The Mission Tumacácori was established by Father Kino at the site of an O’odham village in 1691. Kino brought more than just his religious beliefs with him; he also brought plants and animals that would soon colonize the New World. Kino’s introduction of Old World species into the New World earned him the respect and adoration of the O’odham people, and helped to create a peaceful transition for the Spanish settlers in the Pimeria Alta. They saw that this new religion came with many material benefits, and this helped with their conversion. As part of the Kino Heritage Fruit Trees Project, the Historic Orchard at Tumacacori National Monument has researched and established a genetic legacy of original root stock rediscovered in backyards and fields in Southern Arizona and Northern Sonora, initially brought by the Spanish. Five acres of Spanish-introduced fruit trees were planted by volunteers (Nps.gov). This interpretive effort is encouraged by the National Park Service and the United States Congress, who are supporting efforts to showcase more locally-produced heritage products as a part of the Park Service’s mission.

Design Implications Growth can be encouraged in heritage garden practices by featuring heritage foods at visitors centers and festivals associated with the park (Nabhan 2010). Some heritage species can be grown for other uses besides nutritional; for instance, gourds used for carrying water, or devil’s claw pods grown for the use of their skin in basketweaving. Heritage crops in the Southwest can serve to highlight Mexico’s role as the earliest center for agriculture in the New World, and can reconnect these two neighbors historically and culturally. Heritage gardens can show how each group that immigrated to the area brought their own food traditions with them. It is also important to coordinate with local volunteers and organizations to accomplish large goals for the park. These orchards highlight crops from original genetic stock that were hiding in plain sight in the Pimeria Alta, and creating additional habitats for this genetic legacy can help to ensure their survival. |

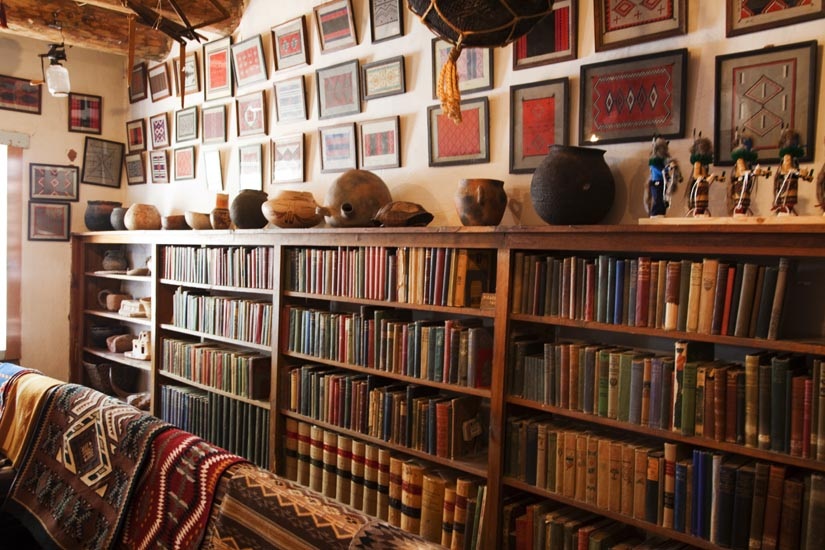

HUBBELL TRADING POST

The Hubbell Trading Post is the oldest continuously-operated trading post on the Navajo Nation. The building and surrounding land was purchased in 1878 by John Lorenzo Hubbell, who turned it into a trading post to serve the surrounding Navajo Nation. He also encouraged a significant trade in Navajo rugs and silver products, and the Hubbell family operated the site until it was sold to the National Park Service in 1967. Historically, Navajo farmed the site, utilizing irrigation built at the site and in nearby Ganado, and the current park has integrated orchards, gardens, pastures and fields, also dealing in wool, piñon nuts, and other items produced by local Navajo families (Nps.gov). They also work to support the cultivation of Churro sheep, an important source of income and a culturally important species to the Navajo. Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site is part of a greater context of Navajo heritage sites in the area, including Canyon de Chelly National Monument and Navajo National Monument.

Design Implications Cultural and historic sites can support local farmers and families by including them as part of the interpretation efforts. As part of an accurate representation of historic agricultural practices, it is important to present a full picture of the crops and livestock raised at the site. Historic agricultural practices can also be practiced at the site currently to aid in interpretation and understanding. Creating a connection between the site in question and other cultural and historic sites in surrounding areas can help to increase the overall interpretive effort, and can enhance visitation to all of the included sites. It is important to recognize that no cultural or historic site exists in a vacuum, and to include the context, where it is possible and appropriate, to more accurately represent the history of the area. |

FOUR MILE HISTORIC PARK

Four Mile Historic Park was once a farm and a stage stop along the Cherokee Trail, the last stop before the traveler would reach Denver. Today, the park is surrounded by city and suburbs in a dense urban matrix. The main house on the site was built in 1859, and passed through several hands, acting as a stage stop and farm, until 1975 when the City of Denver purchased the house and remaining 12 acres of property, and turned the farm into a city park. The park today is a living museum, demonstrating Denver’s pioneer past, with events and programming held throughout the year. Although the park is owned by the City of Denver, it is managed and run by the nonprofit Four Mile Historic Park, Inc., and is supported by a strong group of volunteers. Though the park itself is a historic destination, it is also a landmark along a system of bike and walking trails that travel along Cherry Creek and throughout different areas within the City of Denver. This trail system ultimately connects to a series of trails that travel throughout the entire Denver metropolitan area. Visitors can see kitchen gardens and sniff the herbs; bake bread in wood-fired stoves; feel the heat of the forge where the blacksmith works; or fill the washtubs with water pumped from the well. The site is not just used for education; it hosts art shows and weddings, family reunions and corporate events, all in a historic, agricultural setting (Hartmann 1998). It serves as an important landmark for the city of Denver, but also as a moment in history preserved. The human interest is what draws us to the place, not just a presentation of discreet historic objects lacking in any social context.

Design Implications The location of the park next to a large, vibrant urban area provides a large pool of potential visitors, especially schools and other groups that visit annually. The ‘living history’ component makes literal the connection between the past and the present, providing the visitor the chance to use all of their senses to experience the past. Programming opportunities, as well as the ability to rent out whole or partial sections of the park, make it more than just a historic and educational destination. A project can be owned by the city/state and managed by an entirely different operation. The location of the park is along recreational trails which brings a wide variety of disparate users to the area. Emphasize the people in the story; that is what visitors will ultimately connect to. |

ARIZONA SONORA DESERT MUSEUM

The Arizona Sonora Desert Museum is not just simply a botanic garden or a wildlife exhibit. It combines elements of a zoo, art gallery, botanic garden, aquarium, and natural history museum, all in one site, in order to represent the lushest desert in the world: the Sonoran Desert. The museum itself was founded in 1952 to showcase the plant and animal species in the desert together in ecological exhibits. It is recognized as one of the top ten zoological parks in the world, and currently ranks AS the #9 museum in the world overall on TripAdvisor.com. The park covers 21 acres, showcasing 320 animal species and over 1,200 different species of plants. The park is owned by Pima County, but is managed and run by the museum. The park features special exhibits not seen in other botanic gardens, such as a birds of prey demonstration that takes place almost daily. Today the park is more than just a destination; it hosts research efforts, education programs, and exchanges with museums and professionals in Mexico. Early interpretive exhibits included one demonstrating the importance of water and water conservation in the desert, making the Desert Museum an early pioneer in water conservation and education efforts. The Desert Museum also runs interpretive exhibitions, intended to showcase the ethnology of the region, bringing in demonstrations like Tohono O’odham basketweavers who work next to the materials that they use for their baskets (Desertmuseum.org).

Design Implications Showcasing the context of a plant or animal species helps to aid a visitor in understanding the unique desert ecosystem. Land on which a historic or cultural asset is located can be owned by one governmental entity, and still managed by another, or by a private foundation or organization. Well-trained docents create the opportunity for visitors to have a more in-depth experience of the site. Ethnology and ecology don’t have to be presented as separate entities; they can complement each other, and can strengthen the educational message of both areas. |

DESERT BOTANICAL GARDENS

The Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix, Arizona is a 140 acre garden designed to showcase the plants and animals of the desert, as well as providing research and interpretive exhibits. Only by communicating the unique attributes of the desert can this important ecological niche be preserved. Festivals and special events are held at the park, as well as educational experiences for a wide variety of visitors. According to the garden’s website, “The Garden’s commitment to the community is to advance excellence in education, research, exhibition and conservation of desert plants of the world with emphasis on the Southwestern United States. We will ensure that the Garden is always a compelling attraction that brings to life the many wonders of the desert” (Dbg.com). The interpretive exhibits are incorporated into the trail system of the park, using traditional materials, structures, artifacts, and plants to communicate a full picture of life in the desert for people, animals, and plants alike.

Design Implications Volunteers are essential in the day-to-day operations of the garden, especially for an organization that is not-for=profit. Preservation, education, and conservation all go hand-in-hand, and are essential elements to the overall operating goals. Programming and multiple uses help guarantee the future of the space and can offer an economic boon as well. Offering classes and other educational opportunities give visitors familiarity with the park and its mission, even if they’re not visiting in person. Incorporating ethnobotanic features fully into the fabric of the site can lead to a fuller visitor experience. |

TUCSON BOTANICAL GARDEN

The Tucson Botanical Garden is a small botanical garden located in the heart of midtown Tucson, Arizona. According to their mission statement, “The Tucson Botanical Gardens promotes responsible and appropriate use of plants and water in a desert environment through education and demonstration and provides a place of beauty and tranquility for Tucson residents and visitors” (Tucsonbotanical.org). Within the larger garden, there are smaller areas that focus on specific representations of history and culture, including a historic garden, Native American crop garden, Tohono O’odham Nation garden, and a Hispanic Heritage Garden. Each of these separate areas highlights the unique features and challenges of growing food and other plants in the desert southwest, and tells a greater story of agriculture and garden cultivation in southern Arizona. In addition to the planted exhibits, the Tucson Botanical Garden also offers meals in a small on-site café, a gift shop, butterfly houses, and other amenities. The site is also available for rental for small events and other uses.

Design Implications With smaller spaces, it is possible to demonstrate many different aspects of culture and history with disparate, smaller gardens, and still contribute to the overall story. It is also possible to create many smaller exhibits within a small amount of allotted space. Diversifying the park into different income-generating spaces helps contribute to its overall economic success. As the Tucson Botanical Garden is located in the middle of the city of Tucson, surrounded by residential and commercial properties, it provides an oasis in the city, as well as taking advantage of a large potential user base from which to draw. |

TOHONO CHUL PARK

Tohono Chul Park is a botanical garden and interpretive center located north of Tucson, Arizona. The park was formally established in 1985, and contains a botanical garden, as well as gift shop, nursery, and café. The park is dedicated to highlighting the survival skills that the people, plants and animals of the desert have adapted to thrive in the Sonoran desert environment, inspiring people who live nearby to live in the desert, instead of just next to it. Their primary focus is on the “natural and cultural connections” (Tohono Chul: The Official Guide), which makes it unusual in the region. The grounds contain ethnobotanic gardens, a desert riparian area, and a demonstration garden containing ideas for local homeowners to embrace their desert environment. Though the site is preserved as a park today, it once was home to early settlers to Tucson and their citrus plantations, and archaeological evidence at the site suggests prehistoric occupation as well.

Design Implications It is important to emphasize the connection between the plants and the people of the southwest deserts for a fuller understanding of the history of this region. Although this site contained artifacts from the Hohokam culture, they are not well displayed or interpreted, so visitors may not be aware of the prehistoric inhabitants of the site. A park can be used to display more than just living material; the geology wall displays the geology of the local area, and interprets a more abstract story of what lies beneath visitors’ feet. |

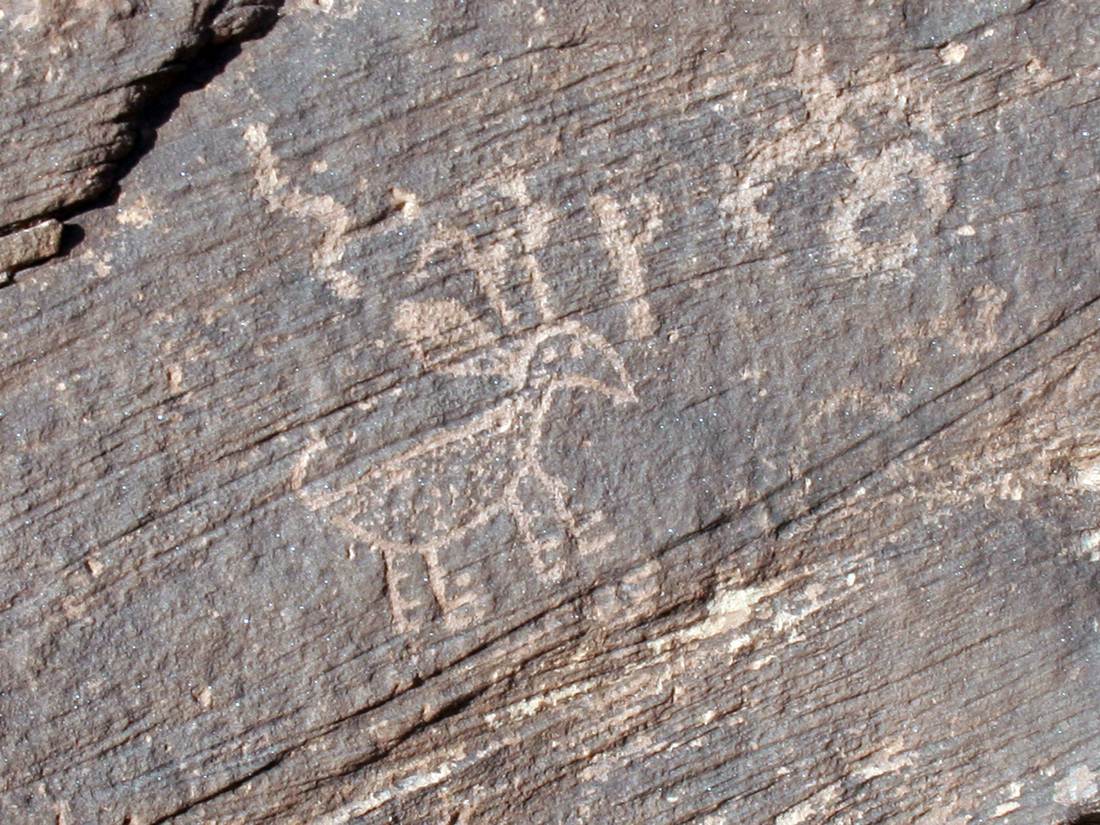

CANYON DE CHELLY

Canyon de Chelly is located on the Navajo Nation in northeastern Arizona. Native Americans have lived and farmed continuously in Canyon de Chelly for nearly 5,000 years, taking advantage of rich, fertile alluvial soils and a reliable source of water. The ancestral occupants were called the Puebloans, and were succeeded by their descendants, the Navajo and the Hopi, who continue to farm in the canyon bottoms. Canyon de Chelly National Monument today sits on the Navajo Nation and is administered by the National Park Service, in conjunction with the Navajo National, as well as the 40 Navajo families that still live within the park boundaries (Nps.gov). The agricultural heritage at this National Park Service-managed site is interpreted by Navajo staffers, who highlight the agricultural traditions of the families that still raise crops and livestock there. Design Implications The design of a site does not just have to be informative; it can also be a source of livelihood for local families. Sites can preserve and interpret agricultural and archaeological heritage as part of a larger cultural history. The park does not offer much in terms of active interpretation or programming, just a static monument. This site is part of a larger cultural context, with links to nearby Hubbell Trading Post and Navajo National Monument, and creating these linkages between sites of cultural and historic importance can increase visitors to all sites, as well as an enhanced understanding of the history and culture of the area. |

HOMOLOVI RUINS STATE PARK

Homolovi Ruins State Park is located near Winslow, Arizona, close to the Little Colorado Rive. The park contains many archaeological sites, including 4 major pueblos, and a number of smaller sites and artifacts. Heavy looting was a problem in the 1960’s, and because of concern about the integrity of the site, the Homolovi State Park was established in 1986 by the Arizona State Legislature to protect these cultural resources. Reconstruction was a common practice in the Southwest, especially during the reign of the WPA, but the Hopi believe that preserve-in-place is a preferable treatment option, and Arizona State Parks also prefers a non-intrusive approach. Preservation of the site is important to future professional and public education. This preservation process is “concerned with curtailing or mitigating factors that have an adverse effect on the integrity and condition of all aspects of a ruined site, including the architecture, all cultural materials and deposit, and the location of the ruin” (Neal 2004:235). Site burial tends to be the most efficient way to accomplish this preservation goal, especially in instances where proper maintenance and interpretation is a problem. Erosion can pose a problem to reburial efforts, but vegetation and a mitigation of erosion factors such as wind and water can largely minimize this issue, which then requires little subsequent maintenance. This is the preservation treatment that was eventually put into place at Homolovi, after excavations and documentation were concluded.

Design Implications Sites that contain archaeological remains need to be able to protect those remains in instances where they cannot be adequately maintained and interpreted to the public. Also important to take into account factors that can affect reburied remains, such as wind and water erosion, while vegetation efforts can help to stabilize the soil. Stabilization and preserve-in-place is preferable to reconstruction, especially on Hopi or other ancestral sites. Arizona State Parks system prefers a non-intrusive approach to site preservation. |

FRUITA RURAL HISTORIC DISTRICT

The Fruita Rural Historic District is part of the larger Capitol Reef National Park in southern Utah. The town of Fruita was established by Mormon settlers in the late 1800s at the junction of the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek, allowing seasonal agricultural cultivation. The orchards at the site, planted by these early Mormon settlers, are almost all that remains of the original town of Fruita. The general management plan for Capitol Reef considers the orchard a historic landscape, and thus plans to preserve them. The orchards contain nearly 3,000 trees (cherry, apricot, peach, pear, plum, walnut, mulberry, and more) that are managed by the Park Service and are offered to local residents and visitors on a pick-your-own basis, where fruit consumed within the orchard is free; the only charge is for fruit taken out of the orchards. This site falls under the National Park Service and Congress’ appeal to increase the amount of heritage products being produced on Park Service land. The pick-your-own orchard is a major destination, not only for those who would typically visit a National Park but for those who are interested in having a taste of this unique piece of history.

Design Implications It is important to reflect the full picture of heritage farming in an area, if it existed. Allowing visitors a taste of history connects them viscerally with the past and the pioneers who brought these fruit trees to the desert, and creates a more interactive interpretive environment. A potential problem and liability is could be created by allowing visitors to pick their own fruit. It also represents a problem in terms of upkeep and maintenance. |

PRESIDIO SAN AUGUSTIN

The original Tucson presidio was established by Army Lt. Hugo O’Connor, after the presidio at nearby Tubac was abandoned, in 1775. Many of the settlers from Tubac had left with de Anza to found the new colony in San Francisco, but those who remained largely moved to the earthen encampment up north. After the fort suffered a heavy Apache attack, high adobe walls were constructed to repel the invaders. The remains of the fort are located in the center of modern Downtown Tucson, where it had been largely torn down. Archeological excavations in 2006 revealed prehistoric pit houses as well as the original foundation for the presidio. Some portions of the fort were reconstructed, including a Territorial-era house, and a mural was painted to interpret the history of the fort. Today the presidio offers programming for interpretation, including school programs, living history days, and the “turquoise trail” that stretches out into the surrounding City of Tucson.

Design Implications Reconstruction efforts need to be either fully realized or not at all – half-effort just dilutes the interpretive message. Programming, especially for school groups and other annual visits keeps the flow of visitors coming. Interpretive efforts that incorporate nearby exhibits and sites needs to be well-executed. A historic site that is part of a greater context in a city or town has a built-in user base, but needs to look at strategies to draw new visitors into the space. |